Harold Schonberg, "Symbolism and Impressionism: Claude Debussy" from The Lives of the Great Composers

"A tout Seigneur, tout l'honneur," runs the French proverb. Honor to whom honor is due. It is not that Claude Debussy lacked honors in his own day. After a slow start, this

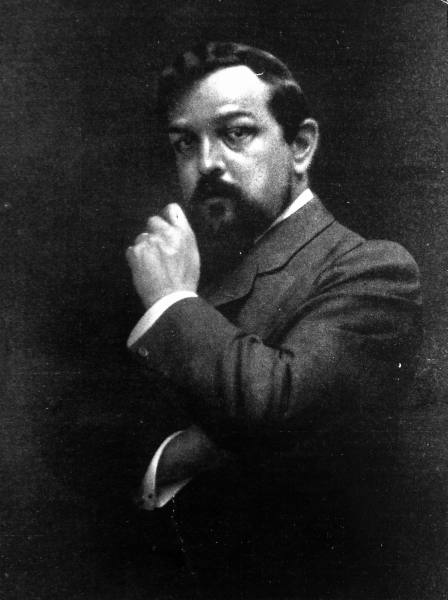

Claude Debussy |

musicien français (so he described himself) was recognized as the greatest French composer of his time. But today he is more than that. He is considered not only the greatest French composer who ever lived; he is considered the revolutionary who, with the PréIude à L'Après-midi d'un faune of 1894, set twentieth-century music on its way. The younger critics are ecstatic now when they discuss the contributions of Claude Debussy. He is, they say, the one who destroyed nineteenth-century rhetoric; the one whose harmonic and melodic innovations led to the breakup of the scale as used in the nineteenth century; the one whose new concepts of orchestration led straight into Webern; the one whose piano music gave pianists more to think about than any other composer since Chopin; the one who reinstated the power of sound for sound's sake: the Rimbaud, the Verlaine, the Cézanne of music. Pierre Boulez, that outspoken exponent of the serial school, has written that certain of Debussy's last works "will be almost more astonishing than the final works of Webern." To Boulez, these late Debussy works are pieces in which all elements of the past have been discarded, pieces illustrative of "the total overthrow of notions that had remained static up to that time" Even as early as L'Après-midi, Boulez says, "all of Wagner's heavy heritage was discarded. The Debussy reality excludes all academism''

Debussy is the greatest of the musical Impressionists, though Symbolist might be a better word. The Impressionist painters-- Manet, Monet, Cezanne, Renoir, Pissarro, and the other members of the Société Anonyme des Artistes, Peintres, Sculpteurs et Graveurs--had three famous shows from 1874 to 1877, and after 1877 the term "Impressionism" stuck. It was derived from a painting by Monet named Sunrise--an Impression. Debussy disliked the term in relation to his own music. As a matter of fact, his tastes in painting were more in the direction of Whistler and Turner than of the Impressionists. The Symbolist poets--Mallarme, Verlaine, Rimbaud, Maeterlinck--meant more to Debussy than painting. Another writer who fascinated him, as he fascinated all the French Symbolists, was Edgar Allan Poe. Debussy worked for a while on an orchestral work based on The Fall of the House of Usher, and in 1908 he actually signed a contra ct with the Metropolitan Opera for operas on Usher and The Devil in the Belfry (and also for one on a non-Poe subject named The Legend of Tristan). But Impressionism and Debussy are forever intertwined, and with good reason. Just as the Impressionist painters developed new theories of light and color, so Debussy developed new theories of light and color in music. Like the Impressionist painters, and like the Symbolist poets, he tried to capture a fleeting impression or mood, tried to pin down the exact essence of a thought as economically as possible. He was far less interested in Classical form than in sensibilité. He was from the beginning a boy, then a man, of sensibilité. Even as a child he had the tastes of an aristocrat. At Bourbonneux's famous pastry shop, his friends would gorge themselves on the cheapest candy, the most they could get for a few centimes. Debussy would choose a tiny sandwich, or a little timbale aux macaronis, or a delicate bite of pastry. Later in life his tastes were equally exquisite. He had to surround himself with fine prints and books. He was a gourmet with a notable appetite for caviar. He dressed to the point of dandyism, complete with carefully selected cravat, cape, and broad-brimmed hat. He knew exactly what he wanted from life and he took it, ignoring the rest. . . .

With these superrefined tastes ran a corresponding dislike of most composers. Brahms meant nothing to him, Tchaikovsky he disliked, Beethoven bored him. He seldom worked in sonata form, the prevailing form since Mozart. He believed that the symphony as a form was dead. "It seems to me that the proof of the futility of the symphony has been established since Beethoven. Schumann and Mendelssohn did no more than respectfully repeat the same forms with less power." His was a music of personal, all but tactile, sensation ("Formless!" cried the academicians), a music that lacked "proper" resolution of chords, a music in which tonality began to be broken up, in which certain twentieth-century ideas of form and technique were first put on display. He was the first of the postWagner composers to work in an entirely new style, and L'Après-midi d'un faune has a place in musical history comparable to the Eroica Symphony and Monteverdi's Orfeo. Each of those epochal works made it clear that the old rules no longer applied.

Debussy thought in a new manner. "I am more and more convinced that music, by its very nature, is something that cannot be cast into a traditional and fixed form. It is made up of colors and rhythms. The rest is a lot of humbug invented by frigid imbeciles riding on the backs of the Masters--who, for the most part, wrote almost nothing but period music. Bach alone had an idea of the truth." There was very little music that Debussy liked, and he was as contemptuous of his French contemporaries and immediate predecessors as he was of some of the revered figures of the past. Massenet was "a master in the art of pandering to stupid ideas and amateur standards." Faust was "massacred" by Gounod, and Shakespeare's Hamlet was "most unfortunately dealt with by M. Ambroise Thomas." Charpentier was "downright vulgar." In general: "Our poor music! How it has been dragged in the mud!"

It was not for nothing that Debussy called himself musicien français [French musician]. Mostly the label was a defiant affirmation of his anti-Wagnerism, and later included his anti-German feeling during the First World War. In any case, his music is the essence of everything French. He once made a lengthy statement on what the Gallic ideals were, comparing French clarity and elegance with German length and heaviness. "To a Frenchman, finesse and nuance are the daughters of intelligence." A French musician should not pile sonority upon sonority: that would be un-French. Artists should use self-control. At that time, Debussy was looking for a libretto. "I am dreaming of poetry that would not condemn me to contrive long and heavy acts, poetry that would offer me scenes which move in their locality and character, and where the characters do not argue but submit to life and their fate." . . .

[Debussy's opera] Pelléas et Mélisande was not a success at its premiere on April 30, 1902, though it caused a great deal of comment. It soon took hold, however, even if it puzzled some fine musicians, especially German musicians. It ran so counter to what the Germans of the day considered opera that there was nothing for them to hold on to. Richard Strauss attended a performance of Pelléas et Mélisande in 1907 with Romain Rolland, who wrote a very funny account of the evening:

Strauss arrived at the end of the first scene and seated himself between Ravel and myself. Jean Marnold and Lionel de la Laurencie [two music critics] sat behind. . . . In his usual uninhibited manner with no regard for conventional courtesy, Strauss hardly speaks to anybody but myself, confiding his impressions of Pelléas to me in a whisper. (Since all the gossip in the papers he has become distrustful.) He listens with the greatest attention and, with his opera glasses up to his eyes, follows everything on the stage and in the orchestra. But he understands nothing. After the first act (the first three scenes), he says, "Is it like this all the time?" "Yes." "Nothing more? There's nothing in it. No music. It has nothing consecutive. No musical phrases. No development." Marnold tries to bring himself into the conversation and says, in his usual heavy manner, "There are musical phrases, but they are not brought out or underlined in a way that the ordinary listener would appreciate." Strauss, rather put out but very dignified, replies, "But I am a musician and I hear nothing."

To this day, listeners conditioned by orthodox singing opera respond as Strauss did.